Assignment 4: Integration

Posted: December 7, 2014 Filed under: Uncategorized Leave a comment2014-11-18_Holland Accessible Path

2014-12-07_Holland Daylight Study

This assignment had two parts: a universally accessible (i.e. Americans-with-Disabilities-Act compliant) path from the public realm to a main entrance of the building in my studio project, and a daylighting study of a room in my project. I’ll take them in turn:

Accessible Path: This assignment came at a good time in my studio design process. I was still finalizing the details of my site strategy, so I was able to incorporate the goal of universal accessibility relatively early on, and integrate it into the main circulation route. I had settled on the idea of dividing the site into three zones: a neighborhood park, a zone of flexible work courts, and a back-of-house service area. The Beck-Cohen building was a natural threshold between the work courts and service zone, and the challenge to create an accessible path created an obvious candidate for a threshold between the park and work courts: a broad pedestrian path that crosses the site, mediating the 24-foot difference in grade between the east and west sides of the site and creating a place where pedestrians can look out over the work courts, which are cut into the slope.

Daylighting Study: At the time of the assignment, my studio project wasn’t developed enough to model a particular room, but since I knew that my building would a long bar running roughly north-south, and thus that it would receive primarily east and west sun exposure, I used the assignment as a way of testing a combination of clerestory windows and vertical sun shades as a daylighting strategy. I built a generic room using my overall massing strategy, and tested it three times: without louvers, with large louvers spaced far apart, and with shorter louvers spaced more tightly together.

Due to a series of cloudy days, I was unable to test the model using actual sunlight, so several of my colleagues and I substituted a directional standing floor lamp. This resulted in overall light levels (as measured in lux) that were far lower than what would be achieved with sunlight, but we were still able to calculate Daylight Factor, since it is a relative measure (ratio of outdoor light levels to indoor light levels).

The vertical louvers are designed to clad the east and west facades of the building. They shade some southern light in the middle of the day, when direct sun exposure might be undesirable in a workspace, and they also may act as light shelves, bouncing soft light into the interior in the mid-morning and mid-afternoon. In the early morning and late afternoon, when the east and west elevations are receiving low, direct sun exposure, vertical louvers are ineffective. If the louvers are working, they should decrease daylight factor in the late morning and early afternoon, and increase it in the mid-morning and mid-afternoon, compared to a louver-free control.

My measured data ended up being pretty messy, which I chalk up largely to my use of a lamp, which fails to replicate the sun’s even, parallel light.) Even so, the louvers appear to be most effective in summer, neutral in spring and fall, and actively detrimental in winter. In fall and winter, there is no difference in effectiveness between the large and small louver schemes. In the summer, however, the small, closely-spaced louvers seem to be more effective than the large louvers (+3 hours of desirable daylight, as opposed to +1).

Assignment 3: Site Analysis

Posted: December 7, 2014 Filed under: Uncategorized Leave a comment2014-10-02_Site Analysis Plates

This assignment represented the first step toward aligning our Building Integration Workshop work with our studio research and proposal. We visited our studio site, near the Belmont Bridge in Charlottesville, to record quantitative and qualitative impressions of environmental conditions. My submission consists of:

– Urban context plan and sections

– Diagrams of annual climate dynamics in Charlottesville, using monthly average data from Climate Consultant

– Experiential site plans of viewsheds, noise levels, and barriers to site access

– Solar obstruction charts, generated by overlaying a plan-view solar path chart on a manipulated panoramic site image

Some observations and conclusions:

– The viewshed diagram was challenging to create. I wish I could have accomplished it using fewer colors, but I wanted each individual viewshed to be clearly legible, while also giving an overall sense of which points on the site are visible from the most other points.

– The noise diagram was challenging for different reasons. Since we were only on the site for a few hours–not enough time to generate meaningful data about overall average noise levels, I took the time in the field to note actual or assumed sources of noise and their relative intensity and frequency. I then used Grasshopper to generate the diagram based on the distance of each point on the site to a noise source. The diagram would have been greatly improved if I had been able to “tag” each noise source with an intensity and frequency, to better distinguish the light industrial building to the west of the site (constant, very low-level) from the rail line to the north (extremely loud, but only six times per day).

– For the solar obstruction charts, I used Android’s built-in Photo Sphere tool, which generates a 360-degree, horizon-to-apex panoramic image. I mirrored the sun chart overlay, since the Photo Sphere images look up from the ground, rather than down at the ground in plan. The result is reasonably accurate, at least going by the position of the sun in charts 2 and 5, whose photos were taken on an early-September morning.

Assignment 2: Case Study – Rolex Learning Center

Posted: December 7, 2014 Filed under: Uncategorized Leave a comment2014-10-28_Holland_Rolex Learning Center

The Rolex Learning Center, a student center, library, and administrative building at Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne, has a deceptively simple structural system. The single above-ground floor sits on an undulating poured-in-place concrete slab, supported by eleven post-tensioned concrete arches connecting to the parking garage below. The roof, a steel and wood frame that runs parallel to the slab below, is supported by over 190 17-cm diameter steel pipe columns on a 9-meter grid. The lateral-load-resisting system was a challenge to indentify: the entire exterior perimeter–and many of the interior walls–are glazed, leaving no place for shear walls or diagonal bracing. It is likely that the loads are borne by a few interior shear walls and moment joints in the columns. I also found photo evidence of at least one diagonal column (not shown in any of the published drawings).

The Rolex Learning Center’s exterior assembly is relatively straightforward, with a triple-pane insulated glass system hung from the steel frame. Notable features include gutters and joints hidden behind aluminum fascia, and an exterior motorized shade structure that absorbs light–and its attendant heat energy–before it enters the building.

Assignment 1: Learning Locally – Campbell Hall 123

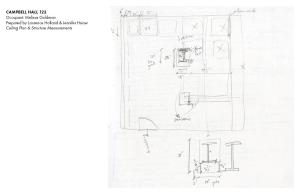

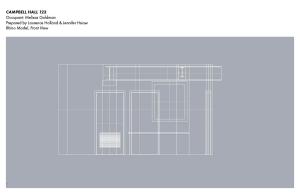

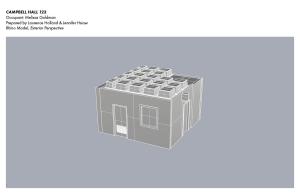

Posted: December 7, 2014 Filed under: Uncategorized Leave a commentJennifer Hsiaw and I were assigned the shop office of Campbell Hall for our building assembly and structure case study. The office presented several challenges, since it is in the basement of Campbell hall and has no exterior walls. This created a two-part challenge–both on the level of the assignment, which was designed around a set of issues (daylighting, ventilation, waterproofing) particular to exterior wall assemblies, and on the level of the room itself, which is artificially lit, noisy, poorly ventilated, and cramped by a large number of pipes and ducts.

Melissa Goldman, the School of Architecture’s fabrication lab manager and the occupant of Campbell 123, has two distinct roles—she supervises the shop and also administers all the shop facilities. When supervising activity in the shop, she is highly active, and needs to have visual and acoustic access to the main shop space outside her office. When she is doing desk work, however, she prefers privacy and quiet. Her workspace works very well for supervising the shop, but not for her administrative work. Given the tension between the desirable conditions for each kind of work, it is difficult to improve her space without negatively impacting at least one of her roles. Based on the illuminance readings and some of the comfort ratings, we were surprised by her general satisfaction and positive attitude towards the workspace. Though she has very few operable environmental controls, her skills and access to the shop give her more agency in tuning the performance of her office space. She also uses furnishings—some custom-built—and clothing as work-arounds. We perceived these measures as a testament to the adaptability of people.

In the course of our investigation, we discovered that while the shop office has no exterior walls, there is actually a small area of the ceiling which, if punctured, would connect directly to the south side of Campbell Hall. We proposed punching through the ceiling in this location as a way of introducing natural light and fresh air into the office. We entertained the idea of an operable skylight, a fixed window that could be walked on by pedestrians at ground level, and a light tube that could gather light from a wider area.

Material Study – Glass

Posted: September 30, 2014 Filed under: Work Leave a comment2014-09-30_Material Study_Glass

cf.:

Building Integration Workshop – 123 Campbell Hall

Posted: September 2, 2014 Filed under: Case Study, Work Leave a commentIt looks like this blog will be an occasional repository for design school status updates and work-in-progress. To kick it off, in our Building Integration Workshop this fall we will be modeling and analyzing the environmental systems of an office in the School of Architecture building, Campbell Hall. My partner Jennifer Hsiaw and I have been assigned the shop office, on the first floor. It is a small room in the rear of the main shop space, with concrete and masonry walls and no natural light. The attached images show our initial measurements (of the room’s dimensions, light levels, temperature, and air circulation) and a 3D model that we will be refining over the next few weeks.

Posted: July 7, 2013 Filed under: Inspiration | Tags: Wittgenstein Leave a comment

“You think philosophy is difficult, but I tell you, it is nothing compared to the difficulty of being a good architect.”

– Ludwig Wittgenstein

Posted: May 1, 2013 Filed under: Inspiration | Tags: Borgmann Leave a comment

“The individual does not shape buildings. We do it together, after disagreements, discussions, compromises, and decisions. …The ways we are shaped by what we have built are neither neutral or forcible, and since we have always assumed that public and common structures are one or the other, the intermediate force of our building has remained invisible to us, and that has allowed us to miss the crucial point: We are always and already engaged in drawing the outlines of a common way of life, and we have to take responsibility for this fact and ask whether it is a good life, a decent life, or a deplorable life that we have outlined for ourselves.”

– Albert Borgmann, Real American Ethics, pp. 5-6

Architecture and the Kantian Sublime

Posted: April 27, 2013 Filed under: Thoughts | Tags: Allison, Geddes, Kant, Wilson 1 CommentThis post is adapted from a term paper (of the same title) that I wrote last fall.

I’ve written previously about the application of Kant’s theory of beauty to architecture, and the apparent belief in some circles that Kantian aesthetics—and in particular Kant’s separation of beauty and utility—has had a pernicious effect on architectural theory and practice. This time around I want to focus on the other part of Kant’s aesthetics: his theory of the sublime. I’m going to try to show that even if Kant’s theory of beauty makes architecture seem like a second-class art, Kantian aesthetics gives architecture a special status among the arts when it comes to experiences of the sublime. Whereas buildings’ usefulness pollutes their capacity for beauty, on Kant’s view, the fact that buildings have purposes is precisely what makes them capable of evoking the sublime.